Queer animality is an alternative framework of being disrupting how Spanish colonialism marginalized the third-gender spiritual figure of the quariwarmi. I argue that animality in Andean spirituality and culture illustrates queerness as a decolonial force despite the repression of indigeneity through the Spanish colonial regime. Seen through this lens, queer animality becomes a radical, fluid embrace of difference, emphasizing how the intersection of queerness and animality threatens dominant power. Indigenous spirituality and embodiment of animality are an active resistance to colonialism because they refute the Western gender binary and fear of the nonhuman. I analyze historical documentation of sodomy in Cuzco and depictions of Andean constellations in conjunction with artwork to demonstrate the intersection of queerness and animality. Contemporary Peruvian artistry pays homage to a queer past, uplifting oppressed bodies through a reclamation of animality. Peruvian artist Javi Vargas uses queer animality to highlight an alternative future, critiquing the colonial influences of masculinity on Peruvian historical figures. Spanish missionaries deliberately suppressed androgynous identities by demonizing sodomy, driving the quariwarmi underground. The jaguar constellation chuquichinchay appears when the quariwarmi is present, and this presence of Andean spirituality intimidates the colonial agenda when manifesting itself through a gendered and animalized power. The radical renditions of notable Peruvian and Andean figures as queer and animalized contribute to the vision of an alternative future where marginalized bodies are honored and celebrated. In the context of contemporary Peruvian art, queer animality therefore represents a transformative outlook on identity, establishing that beyond the human, there is a liberatory future.

Incan Gender Roles Within Andean Cosmology

Primarily, diverse gender roles and forms of worship are notable in Incan societies. The Incan empire usurped the Chimú society around 1200 CE and began to decline during the Spanish invasion in 1532. Their capital city, Cuzco, represented Incan advancements in architecture and urban planning. As the Inca spread throughout the Andes, their ideological and religious beliefs contained similarities to the local Andean peoples but differed in their primary worship of Viracocha. Viracocha, the “androgynous divinity” was the god of highest divinity and deepest reverence. A perplexing contrast is raised in the overt delineation between male and female roles when a being transcending binary genders takes the highest seat in the cosmological order. This intriguing identity is explored with other deities embodying this fluctuating gender role. Incans believed Viracocha to be the creator from which all other deities arose.

From this creator, the organization of the Incan spiritual world was born. Existing through two avenues, the Sun and the Moon were divided into male and female realms, respectively. The male realm under the Sun also encompassed morning Venus, Lord Earth, and Man. The female realm followed a similar path, with Venus at night, Mother Sea, and then Woman. Pachacuti Yamqui, an Indigenous chronicler of Andean knowledge, first documented this conceptualization of the Incan cosmos. This construction of cosmological identities directly influenced the organization of labor within Incan society, as the Inca uniquely allowed their subjects to remain within their kinship groups when they were conquered and absorbed under the new rule. In succinct organization, “local chiefs were tied into Cuzco government as middlemen, and their political role was encoded in Inca cosmology. The Inca as the Sun’s son shared Venus’s position, and local chiefs (or headmen) claimed Venus as their divine father.” The Inca Empire sustained its power and expanded its realm by keeping existing power structures in place while implementing control through this new system. Giving subjects the illusion of freedom while laboring for the greater ruling power maintained the organization of the Incan government, markedly through similar spiritualities.

Kinship communities determined how gender relations were constructed. These kinship ties, called ayllu, represent a familial circle but expand to encompass extended families and local ethnic communities. Men and women received ayllu resources similarly, through parallel transmission from their kinship lineage. The daily activities of Andean peoples were essential in constructing cultural gender roles. Labor organization was divided by gender, but the boundaries were never stringent enough to prohibit a woman from doing a man’s task, or vice versa. Women primarily did textile work, like weaving and spinning. Their priorities included childcare and housework, notably not to serve their husbands but to ensure the livelihood of their community. Men were entrusted with fieldwork, construction, and preparing for combat. While gendered activities were not restricted, these tasks were deeply intertwined with Andean gender ideologies.

Cosmology and gender are innately intertwined. Women in the Incan world are tied to the Moon, and men to the Sun. However, a third space remains. The fluidity of the Andean cosmos creates an oscillating pathway in which binary gender roles fade away. Quariwarmi (men- women) were third-gender subjects who maintained an androgynous position within spiritual practices. This androgyny was systemically obscured and dismantled from within the Spanish colonial realm, as it fundamentally averts binary gender roles. Horswell details quariwarmi positionality as a “visible sign of a third space that negotiated between the masculine and the feminine, the present and the past, the living and the dead.” This third space radically deconstructs the binary world cemented through Spanish colonial rule. The ability to move freely within categorical distinctions celebrates and emphasizes the power of quariwarmis, as this fluidity is not conceptual but embodied through individuals essential to the community.

The merging of quariwarmi identity with the cosmos is no accident. In the human mind, the cosmos is a malleable concept due to its ambiguity and vast openness. Meaning is created subjectively and changes depending on interpretation. Androgynous forces are decolonial by definition because it is the absolute refusal to ascribe to a norm. Norms remain subjective to each group that details and follows them, but androgyny remains undefined by a singular perspective. The role that quariwarmis played as spiritual guides further inscribes the position of these shamans in the spiritual order.

Suppressing Androgyny: Queer Erasure Within the Spanish Doctrine

Few roles are as culturally embedded as revered spiritual figures. A futile attempt by the colonial order intended to obscure this livelihood, but spiritual practices remain as their believers exist. With this, “Transvested Andeans introduced a crisis into the Spanish patriarchal paradigm because the third gender’s symbolic rupture of the gender binary served the purpose of creating harmony and complementarity between the sexes and invoked the power and privilege of the androgynous creative force.” This power is threatening and dangerous to the colonial hegemon because it comes from an unregulated realm; the profound invocation of “power” is intentional. If power stems from an unknown force that the agents of domination cannot replicate, it is unable to be positively harnessed and will be destroyed. The eventual naming of quariwarmis as “sodomites” was key in the erasure of this third-gender subjectivity in written colonial histories. The third gender in Andean culture is vital to the comprehension of spirituality, as this identity represents a physical manifestation of subversion and alternative realities to the binary norm.

Colonial leaders in the Andes attributed any queer behavior to sodomy, as they considered any deviation from the gender binary a sin. Spanish colonizers felt threatened by Andean spirituality in their celebration of non-traditional gender roles that they deemed all identities falling outside of the man/woman binary as sodomites. In the Bible, sodomy is marked as a nefarious sin, a betrayal of morality so grave that it renders the subject irreversibly tainted. Through a colonial lens, the staunch celebration and presence of “sodomites” in Andean culture threatens Catholicism as the new order because these individuals do not perceive their culture as immoral. In fact, “There is no recorded word for sodomy in the indigenous languages that does not reflect Western attitudes.” If colonial powers cannot convey their disdain for these practices, it is significantly more difficult to convince colonized subjects of their dismay. Even so, this cultural disconnect did not stop the Spanish from perpetrating their persecution of alleged sodomites.

Citizens of Cuzco employed deception as a resistance tactic during colonial interrogations. These interviews were conducted by the Toledo viceroyalty (1569-1581) to extract information about jeopardizing aspects of Andean culture to the colonial reign. Francisco de Toledo’s regime represented a justification of Spanish colonialism, framing Indigenous Andeans as needing salvation from the Inca empire. He postulated the idea that if colonial leaders attempted to understand how Indigenous Andeans dictated their lives, their methods of control and subjugation would be more successful. Horswell writes, “The colonizers’ search for these ‘secrets’ would aid them in colonial governance, religious conversion, and personal enrichment.” Within these interviews, it is difficult to discern the attitudes of each informant, as their answers were homogenized under the interviewer’s methods and translations. Among other questions about the functioning of the Inca empire and how Incan subjects were treated, Toledo included a question about the prevalence of “el pecado nefando de sodomia”, the nefarious sin of sodomy. The immediate and innate determination of sodomy as a sin stems directly from Spanish Catholic teachings. Even within the initial inquiry, the preface of sodomy and any form of queerness is viewed negatively. In asking this question, this administration perpetuated the continual and final goal of colonialism in the Andes–the eradication of bodies and perspectives that deviated from the normative gender binary.

However, the responses of the interviewees refuted the expectations of the interviewers. Only vaguely addressing the concept of sodomy, the interviewees mentioned the “orua,” individuals who are men but act like women. This was as far as any “nefarious sin” described in testimony. Still, mentioning the orua could have been a reference to quariwarmi, who possess these dualistic gender traits. Horswell describes this obfuscation as “[A] mimicry of the informants can be characterized as a distancing strategy that protected any ritual connection that may have existed between the third genders and same-sex praxis.” Electing to vaguely inform officials in power about these identities is a resistance tactic, even if additional sacred positionalities were revealed. Misleading colonial authorities is a significant form of resistance, altering the future of marginalized groups.

Etching Femininity in Peruvian History

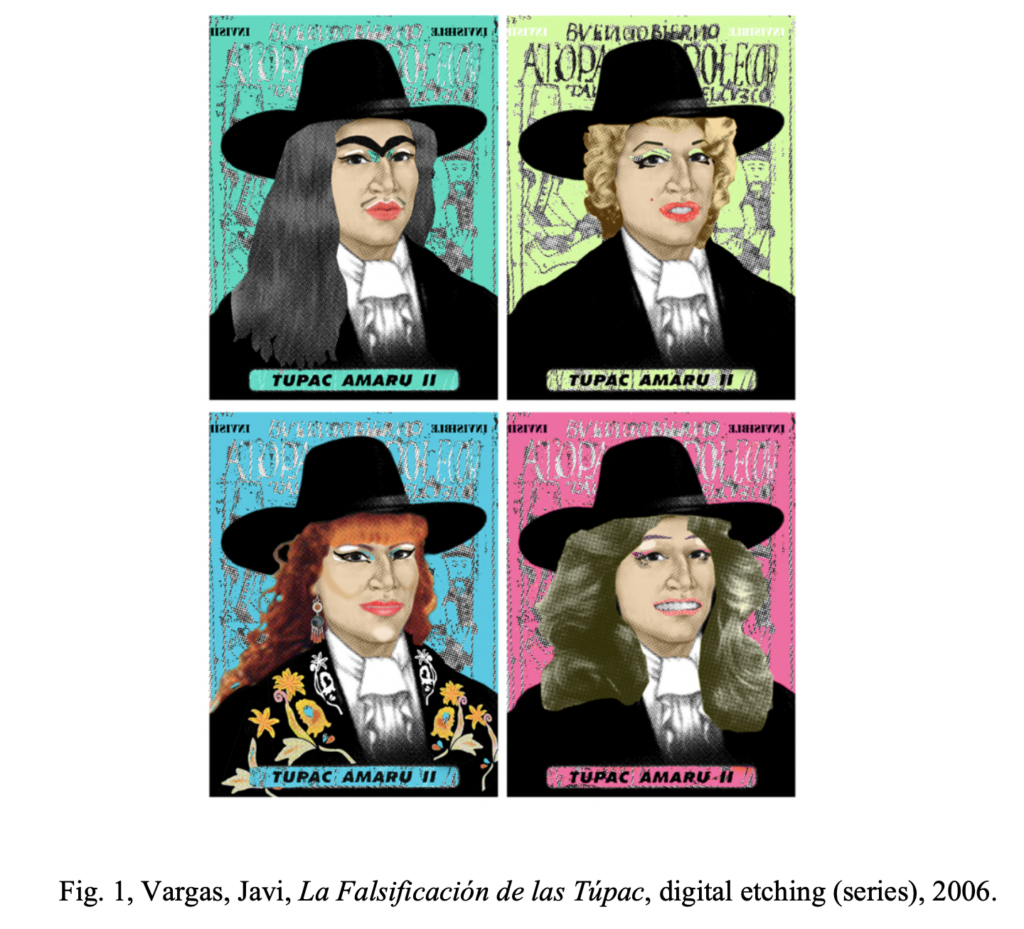

The iconic figure of Túpac Amaru II is a staple within modern Peruvian culture. Amaru II led “the largest Andean insurrection against Spanish colonial rule in 1780.” This insurrection was among many conflicts leading to the liberation and establishment of Peru as a nation in 1821. Danielle Roper in her essay “Queering Túpac Amaru II: Travestismo as Methodology and the Re-imagination of Andean Cosmology” explores the concept of the hyper- masculinization of Amaru II in Peruvian culture through her analysis of Javi Vargas’ piece, La Falsificación de las Túpac, and how this intentional feminization and travestismo of an iconic cultural figure dismantles expectations of hegemonic gender identities. Túpac Amaru II’s fierce masculinity and breathtaking feat against the Spanish reign cemented him as an unforgettable figure in Peruvian history. His image is marketed toward the Peruvian public as an icon of staunch masculinity, authority, and power. However, this steadfast masculinity pushes norms of machismo, stemming from the patriarchal ideology of male supremacy. Imposing this imported masculinity erases the fluidity present in Andean gender relations.

Amaru II claimed to be a descendant of Túpac Amaru I, the last Inca King executed by Spanish colonizers. Amaru II trademarked this identity during his rebellion and used his indigeneity to claim a return of Indigenous power to a colonial realm. This idea was co-opted again by the rise of Juan Velasco Alvarado, who rose to power through a coup and spearheaded the leftist military government from 1968 to 1975. Velasco Alvarado’s goal was to uplift Indigenous identities, advertising his campaign as a second coming of Amaru II’s initial uprising. Velasco Alvarado made a popular reimagining of Túpac Amaru II’s image imperative to his rule, conveying the revered masculinity and indigeneity he sought to represent: “The regime cast him as a racialized masculinity who symbolized the ideals of racial uplift and the impending of an oppressive racial order.” This intentional masculinity by Velasco Alvarado is particularly compelling, as colonial powers often feminized Indigenous men as a means of subordination. When transposing femininity onto masculinity, the vigor and authority associated with masculinity are erased, replaced by inherent submission.

Within La Falsificación, Vargas displays a feminized Amaru II through four iconic patrons of femininity. In this piece, it is imperative to note the usage of the terms travesti and travestismo instead of the English word transgender. Identifying as travesti is different than being transgender, as being travesti is embarking on a journey to achieve “femininity, in its broadest sense, as its final destination.” Vargas utilizes famous white and Latina female figures such as Marilyn Monroe, Farrah Fawcett, Frida Kahlo, and Dina Páucar in his queering of Amaru II, where their performance marks the initial imagining of a travestismo reality. Roper argues that the transposing of femininity on Amaru II and the masculinization of the female figures is a double queering. “As travestis use fabrication, fiction, and disguise to destabilize and to reveal the constructedness of normative gender categories, so too does a travesti methodology use falsity and artifice to trouble official imaginations of national identity.” Within this lithograph, the images of Las Túpacs are transposed on a drawing of the execution of Túpac Amaru I by Indigenous historian Guaman Poma. Poma’s analysis of Spanish rule in the seventeenth century is another form of radical critique, as it is the longest review of the colonial reign by an Indigenous figure. Transposing colonial and Indigenous imaginings of the past and future introduces a new realm illuminated through subjugated groups.

Furthermore, Vargas’ emphasis on Las Túpacs over Poma’s drawings intentionally frames a new narrative of Andean history, establishing a queered archive. This radical perception of history is how utopic histories are created and exactly what Vargas intends with his art: “I start to dream of a parallel…kind of world where the history is different, where Túpac Amaru is not a macho but is a drag queen, and history is reversed, narrated in different ways.” Imagining this queer utopia through La Falsificación represents more than a critique of imposed colonial masculinity, it displays an alternative reality where popular history can exist through a lens of ardent femininity.

Light in Darkness: Queerness in the Cosmos

A focal point of the Andean cosmovision is the representation of deities within the night sky. Attributing meaning to the vast and entrancing cosmos tethers spiritual beliefs to the Earth, as shown through physical manifestations of sacred beings. The deity chuquichinchay is expressed through a representation of a jaguar as the patron of third-gender individuals. Chuquichinchay is a constellation depicted in the Andean sky, remaining a guardian in the sky and on Earth. This jaguar deity appears during moments of ritual significance in Andean culture when the quariwarmi are present. Animals are often seen as spiritual guides and protectors. Their respectability and admiration stem from their ability to remain in this transcendental form of embodied presence, shifting from ritual significance to physicality. Allocating spiritual guidance to individuals who also surpass the gender binary reflects this animality. Aligning queerness and animality in the cosmos uplifts this unconventional combination.

In addition, the shamanic capabilities of quariwarmi illustrate how the position within, outside, and between the gender binary transcends boundaries and maintains a stronger connection with the cosmos. Third-gender individuals rise above the material and cosmological world, flowing between the x and z axis, unable to reside in a singular location. Much like the night sky, it is impossible to view gender along a straight axis, operating on a line from male to female. Reimagining this axis as a spectrum, an encompassing perspective of visualizing existence mirrors the pre-colonial cosmos. The Moche culture of Peru viewed the cosmos through a circular spectrum encompassing elements of the Earth and the sky. They viewed gender on a scale of femininity to masculinity, emphasizing and encouraging this fluidity. Employing a circular understanding of gender demonstrates how the quariwarmi maintained a cosmological and spiritual purpose.

While present in Andean culture, this conceptualization of gender is completely radical to colonial ideologies. A colloquial understanding, celebration, and acceptance of third-gender individuals are absent within colonial cultures. Accepting a third gender within a cultural history refutes the colonial intention of staunch binaries and rigid social structures. Continuing to discuss the presence of quariwarmis within the Andean archive further immortalizes this role, as it unearths the intentional suppression by the Spanish regime. In the context of Andean studies, queerness references identities like third-gender individuals who transcend gender binaries through their existence. While the idea of a third gender can be seen as queer from an outsider’s perspective, this identity does not have the same irregular connotation within Andean communities. Even though quariwarmi were not viewed as “queer” by Andeans, the mere existence of an individual refuting a binary gender role exists as this otherized representation. Working to understand this identity from an outside perspective demonstrates the initial queering of the quariwarmi.

To be queer is to be defined and seen through the fluidity of otherness. Otherness is to reject the cis-gendered and colonial hegemon that regulates and determines which bodies and ideas are embraced and celebrated. José Esteban Muñoz, in his book Disidentifications, elucidates the concept of disidentification, encapsulating the transitory positionality of queerness. Unbound by norms of societal governance, “Disidentification is, at its core, an ambivalent modality that cannot be conceptualized as a restrictive or ‘masterfully’ fixed mode of identification.” Queerness is a liberatory practice because it exists within the margins and without the comfort of the heterosexual cisgender agenda. It evolves and fluctuates with the inherent understanding that the power of queerness resides in disidentifying from normative ideas of gender and sexuality. “Otherness” is similarly unidentifiable through the broad nature of a nondominant positionality. With this, the quariwarmi is a queer figure embodying disidentification because of the refusal to stand as male or female, live through one corporeal figure, and exist as a human or animal.

The Animal Within: The Colonial Construction of Race

Measuring the spectrum of humanity within colonization is marked by the subject’s proximity to whiteness. María Lugones explores this concept in “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” where she argues that Indigenous women and men are incapable of being colonized because they are not viewed as human to begin with: “No women are colonized; no colonized females are women.” This excerpt highlights the double othering placed on the bodies of Indigenous women, who face avenues of oppression from all sides. Their initial marginalization is through their gender, immediately deemed subordinate by the patriarchal and colonial hegemon. Secondly, failing to recognize colonized females as women introduces the racial aspect of colonization. Colonial powers postulated that Indigenous bodies could not be colonized because of their inhumanity and, thus, animality and their inability to assimilate into “righteous” European culture. The further the individual strays from the accepted norms of behavior, placidity, and civility, the closer they are pushed to exile. The gap between human and animal narrows as the new identification is from man to beast. This exile marks the person as irredeemable, as an inhuman subject cannot be colonized if they are not human.

It is necessary to highlight the racial aspect of Andean subordination by the Spanish. The justification of conquest was initiated through the creation of race, dividing the colonizers and the colonized. These categories were devised on their proximity to whiteness and basis in morality, locating Indigenous communities as the furthest from whiteness and closest to animality, inhumanity. Lugones states, “Indigenous peoples of the Americas and enslaved Africans were classified as not human in species–as animals, uncontrollably sexual and wild.” In perpetuating racial categories, animalistic traits were pushed onto Indigenous communities due to their “uncivilized” behaviors. Once again, Indigenous figures could not be colonized because they were not perceived to have any humanity.

Additionally, Mel Chen describes animality as built around and from race and sexuality. This proximity to animacy coincides with racial identity perpetuated by colonialism. The discussion of race is impossible without considering why these concepts were created and how they exist to divide and isolate Indigenous communities. Chen writes, “Animal figures, in their epistemological duties as ‘third terms,’ frequently also serve as zones of attraction for racial, sexual, or abled otherness, often simultaneously.” Chen’s identification of third terms to describe animal figures is notable in the consideration of the animality of the quariwarmi, in that this third gender is represented by a jaguar. When animality is detracted from its harmful reputation, it harmoniously displays a portrayal of interspecies connection.

Altogether, the presence of animality within an Indigenous cosmological figure shows how these aspects are inherently intertwined because of their shared embodiment of fluidity, deviance, and power. Combined, they gain power because they do not fit neatly into one category. Fluidity and deviance are seen through the presence of both the chuquichinchay and quariwarmi in times of Indigenous ritualistic practice. Here, Muñoz’s idea of disidentification continues to describe why the interwoven practices of animality, queerness, and cosmology are radical: “Disidentification is a step further than cracking open the code of the majority; it proceeds to use this code as raw material for representing a disempowered politics or positionality that has been rendered unthinkable by the dominant culture.” Otherness is relational because of the shared experience of existing outside the binary and dominant culture. Animals, humans, and the stars carry each other within them; one aspect cannot exist without the other. Therefore, the celebratory intersection of animality and queerness in Andean spirituality reclaims the negative connotation of otherness imposed by colonialism.

Deviant Peruvian Art: Embodying the Animal, Living as One

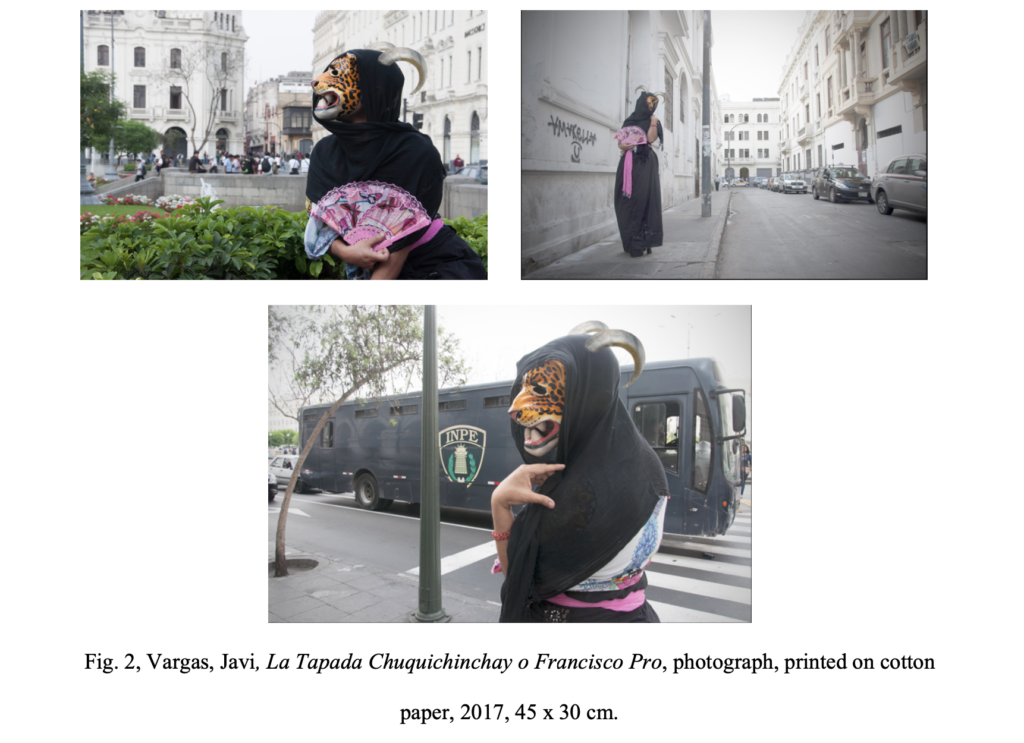

Vargas intersects animality and gender through his photo series titled “La Tapada Chuquichinchay o Francisco Pro.” This piece displays the manifestation of the chuquichinchay in the material world and the representation of alleged sexual dissident Francisco Pro. Denoting the chuquichinchay as a tapada unveils an intriguing link between animality and femininity in colonial Peru. Tapadas were upper-class women who covered their faces with a veil to avoid surveillance by their husbands and families. Elusiveness lingers in the gaze, revealing only the eye, and inviting the onlooker to fantasize about what lies beneath the fabric. Tapadas were often sexualized because of this mystery and allusion, as this restricted visibility lent itself to seduction. The sexualization of the feminine body is ubiquitous, but within this context of the intended gaze, it opens additional avenues of analysis.

In this series, the alleged feminine figure is not solely a human woman but the chuquichinchay, with a jaguar face and human body. Wearing the typical black veil, the chuquichinchay has half of its face uncovered, rather than the singular eye. Additionally, the goat horns demonstrate a doubly animalized version of the tapada, displaying interspecies conjunction and subversion. Since these third-gender subjects were under prosecution by the colonial government, the intentional obfuscation of the chuquichinchay through the tapada illustrates the elusiveness and seduction of these figures. Embodying the shielded nature of the tapada while existing as the chuquichinchay would help to protect these figures from persecution and systemic erasure. Revealing just enough animality to intrigue the onlooker but keeping the rest of the body hidden aligns with the cultural role of the chuquichinchay and the presence of the jaguar deity during ritual ceremonies.

Furthermore, Francisco Pro was arrested in Lima in 1803 for dressing as a tapada woman. During his trial, he was found guilty of sodomy for his expression through tapada clothing. Even though Pro did not fit the actions of a sodomite, the act of crossdressing and deviating from the colonial gender norm ostracized him with the new label of the “other.” The portrayal of the chuquichinchay through the tapada and Pro’s persecution because of his alternative gender expression displays how, even if intentional, the feminization of masculine bodies is used as justification for persecution by colonial powers. Through both these representations, the tapada is queerly animalized, from the modern depiction of the chuquichinchay and the ascribed sodomy to Francisco Pro.

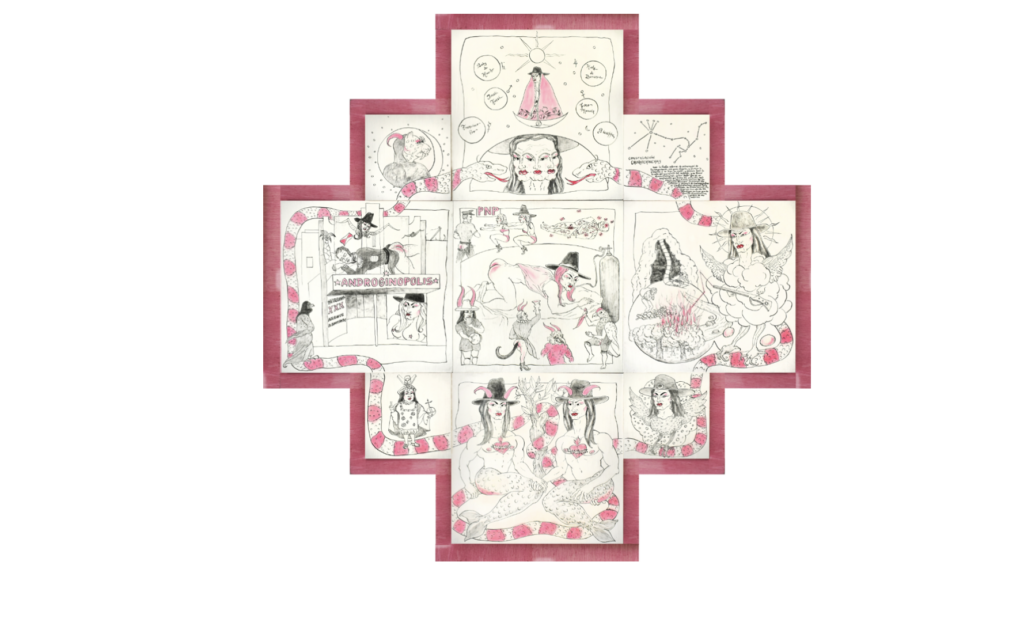

Chakanas proudly presents an amalgamation of Vargas’ work, and the conceptualization of this paper links his various queered Andean fantasies into a totality of imagination displaying this queer metamorphosis. Beginning with the arrangement of the drawings, each piece is arranged within the chakana, the Andean cross. This cross incorporates all realms of the Andean world, uniting the cosmos with the material Earth. Many Túpacs are scattered throughout the collage, all feminized and many with animal traits. Each Túpac still contains the strict trademark of his masculinity: the wide hat and strong bone structure. However, the Túpacs are feminized and surround the cross, touching all aspects of the Andean world with this queered imagination. The critique of these revered figures in Peruvian history swallows the Spanish desire to subdue animality and femininity. The heavy avian representation within the animalized figures is pertinent to Andean mythology, as the condor represents the imagined future. The feminized and animalized Túpac blatantly represents queer animality and its location within this queer utopia.

Encircling the chakana, the two-headed snake (amaru) weaves through every aspect of the cross. It encapsulates and connects all corners, showing that all cultural aspects are interconnected. Andeans saw the two-headed snake as a deity who ruled the Andes and protected them from threats. As the amaru envelops the feminized Túpac, it shields these vulnerable figures from colonial harm. Using animals as protectors instead of humans highlights the significance of interspecies unity in the face of subjugation and terror. To untangle and deviate from the colonial norm, aligning with similarly ostracized nonhuman figures strengthens otherized communities.

Finally, the reclamation of “androginopolis” critiques 18th-century Lima in the perception of male Limeños as feminized and temperamental. In Chakanas, androginopolis is an adult movie theater showcasing the sexual submission and overt feminization of hyper- masculinized icons. Lying on his stomach with his backside exposed and raw from sexually submissive activities, Simón Bolívar, esteemed military general, exists within the realm of dissidence in his pursuit of sinful sexuality. Androginopolis represents a queer utopia in which masculinized figures can explore femininity and submission through an empowered act of resistance toward Spanish colonial morals. Here, the queered Andean future is proudly displayed through this compilation of erotic care, reclamation, unity, and remembrance.

The Past is the Future: Queer Animality as a Utopia

This essay explores how queer animality is a subversive framework refuting colonial ideals of gender, employed through the Andean spiritual figure, the quariwarmi. Andean cosmological order determined gender roles in pre-colonial Peru, where women and men worshipped gods that represented femininity and masculinity. Quariwarmi individuals represent a third space of spiritual fluidity in Andean cosmology, causing an ideological crisis in colonial Peru by disturbing the gender binary. The Spanish religious doctrine feared any queer figures, systemically targeting sodomites. Vargas’s feminization of Túpac Amaru II subverts masculine ideals of power, critiquing Velasco Alvarado’s presidency. The jaguar deity chuquichinchay represents the Andean third gender, illustrating the cosmological presence of the quariwarmi. The fluid androgyny of the quariwarmi refutes binary gender roles, rejecting colonial expectations. Queerness is inherently fluid and transitory, moving above and through dominant paradigms. Colonialism intentionally dehumanizes and animalizes Indigenous folks, but the quariwarmi embodies this reclamation of animality. Vargas’ portrayal of the chuquichinchay as a tapada reveals another link of animality to femininity, illustrating a dualistic subversion. Javi Vargas, in his subversive performance art and drawings, incorporates Andean spirituality in a depiction of queer animality as a utopic future, where Spanish coloniality is obsolete.

What if we were animals? What if that is our future? Learning from the past and detaching from colonial degradation will initiate this journey. Looking beyond the human, cosmologically and animally, is a profound act of resistance. To look within, we must look beyond ourselves and our bodies, calling upon the guidance of those before us, unlike us, but within us. The cosmos is an undulating facet of knowledge and a beacon for this praxis. To queer our past provides a path for queering our future, sowing this queer utopia.